Rafaela Prifti

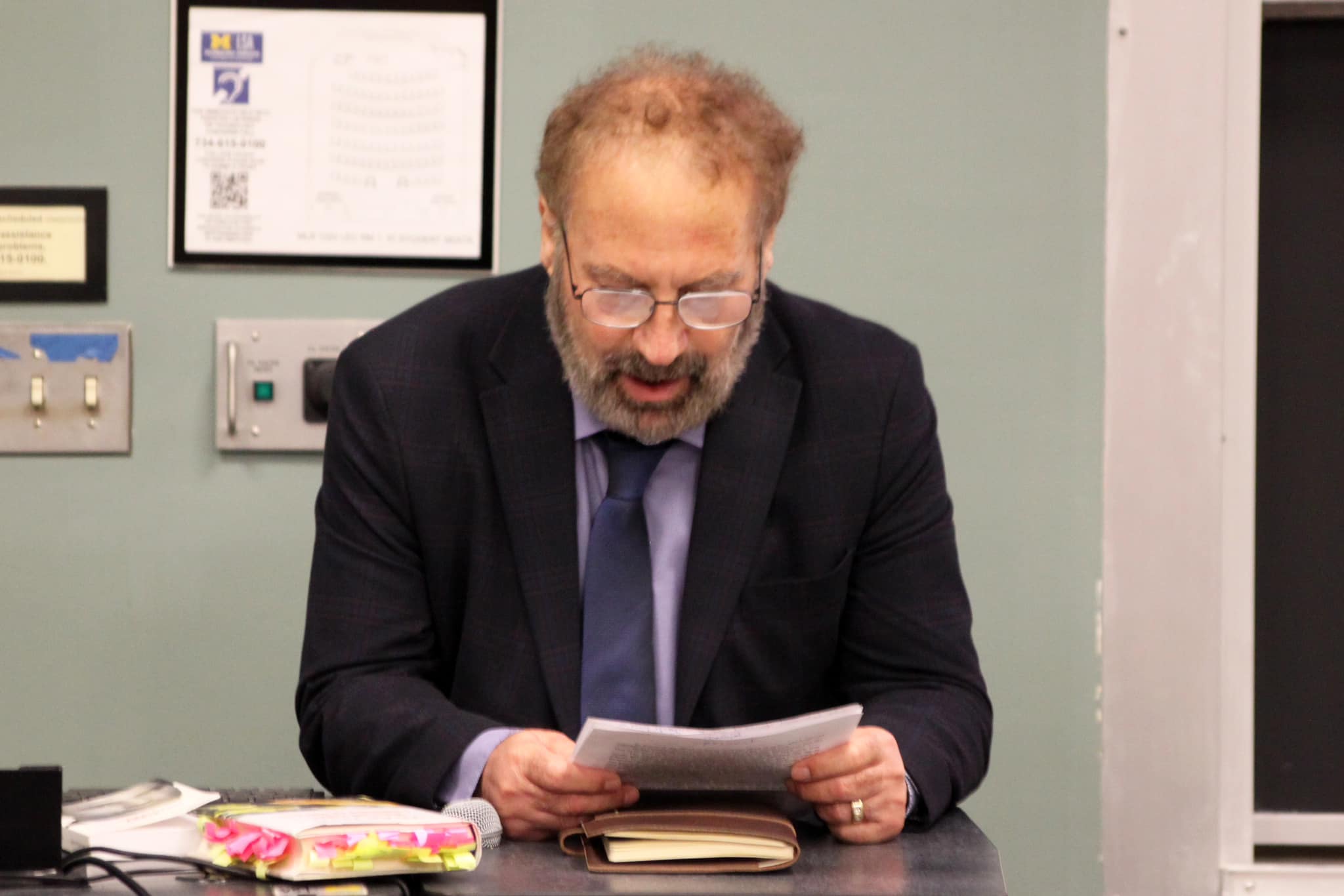

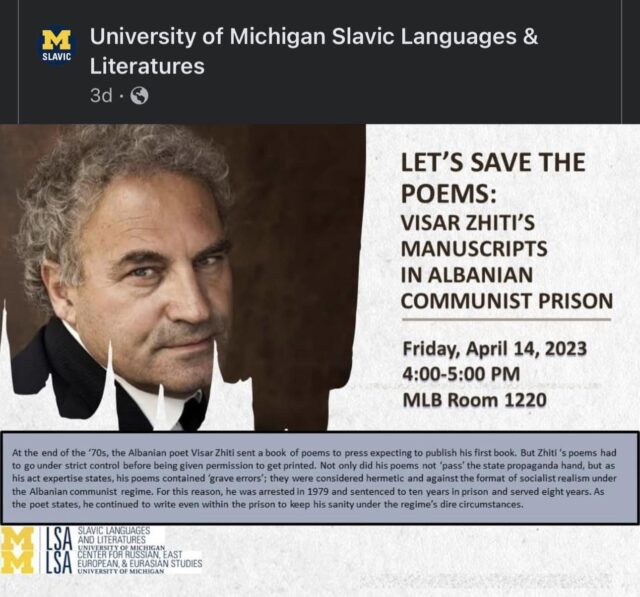

At Michigan University Ann Arbor “Lets Save the Poems” was a one-hour talk by Visar Zhiti, a celebrated Albanian author and prominent poet, also a survivor of imprisonment in communist Albania. The recipient of poetry’s grand prize of 2022 “Le Grand Prix De Poésie” presented an insightful exploration of the quest for freedom that was well incorporated and weaved into the Albanian Literature of Exile coursework, created and taught by Dr. Lisandri Kola since 2019 in Language Science Arts at the Department of Slavic Languages in the prestigious two-hundred-some-year old research university in the Midwest. Dr. Kola says that “Visar Zhiti is the first guest speaker he has invited to the class.” At a quick glance of the poet and his works one could understand why. In literature, Zhiti embodies a rarity that could be hard to find in the category of rarities. He is simultaneously both unique and representative of the spirit of resistance from inside out. Visar Zhiti was condemned and thrown in prison for over a decade in communist Albania for his free thinking! In this respect, his story resembles many imprisoned poets and writers of countries behind the iron curtain. In a relentless search to be free, poetry became his form of self expression that cannot be bound. On the one hand, Visar Zhiti is one of them. His books have elevated to prominence the body of work created at or stemming from within prison walls by those who were condemned by the regime not to be seen, not to be heard and particularly not be allowed to share the “free thinking” with the fellow men! In what are effectively acts of defiance towards the oppression, his manuscripts were smuggled out of prisons as did other fellow poets who suffered similar punishments by the regimes in East Europe. On the other hand, there is only one of him. The Albanian poet saved the poems against all odds and, in the end, overcame defiance with love. Visar Zhiti stands out even in his story of persecution given the minute number of poets from the Eastern European block that got the poems out of prison through memorization, as he did. Because of their visibility in society and ability to shape public opinion, prominent literary figures were among the first targets of Communist repression, torture and incarceration,” writes the publisher of “The Walls Behind the Curtain – East European prison literature, 1945-1990” by Harold Segel, professor emeritus at Columbia University. Precious few publications are available in English on the work of imprisoned writers by countries of the Soviet bloc “who wrote during or after their captivity under communism” notes the publisher pointing at “Authors such as Alexandr Solzhenitsyn (that) famously documented the experience of internement in Soviet gulags.” Visar Zhiti is featured along remarkable novelists, poets, writers such as Vaclav Havel, Eva Kanturkova, Adam Michnik, Milan Šimečka, Paul Goma, Tibor Dery and more.

Rea Hajredini, a sophomore student, who participated at Friday’s event said that “the Albanian writer and poet Visar Zhiti spoke of his experiences in prison under the Albanian communist regime and how writing gifted him with determination and a willingness to persevere.”

Although Zhiti speaks of his own manuscripts by drawing from personal experience, the resounding message of defiance across the communist block at the time is heard clearly at Ann Arbor’s auditorium. “His work is recognized as a symbol of literary resistance against communism in Eastern European countries. In this context, he is as much East European as he is an Albanian poet,” says Prof. Kola, adding that he “is very pleased with the whole event, Zhiti’s lecture and the follow-up session that it prompted in the class.” Dr. Kola, who is also a published poet, has collaborated with Zhiti in a recent project that dwells deeper into the political culture and the key questions that the present literature grapples with in Pyetja Nr. 19 Tirana, Onufri, 120pp (Question Nr. 19) Although inviting guest speakers to his class is not “an established practice,” Lisandri Kola points out that the class benefited measurably from “Zhiti’s presentation (that) brought into focus his own prison manuscripts, through valuable archival materials, rare footage, translated poems as well as some original works.”

Indeed the student audience responded to the message of the poetic journey reinforced by the visual presentation and powerful delivery. Reflecting on the talk, Rea says that “it was truly inspiring to listen to Visar Zhiti speak of his efforts in writing poetry during his time in prison and to hear the emotion and passion in his voice as he shared the traumatic experiences of his past. It was intriguing to hear him speak about the challenges and hardships he faced in prison, but it was even more inspiring to hear that Zhiti was able to overcome this suffering through poetry. I found it very fascinating how he was able to create poetry in his mind during times when he had no access to paper nor writing tools.”

One of the most impactful images for students was the poet’s smuggling the poems out of prison, hidden in articles of clothing at the visitation times with his family. “Later on, Zhiti secretly wrote poetry and hid the papers in clothing and inside the straw mattress of beds. During visitations with his family, he would quickly pass his writing to his family for safekeeping, which proved that prison literature was able to escape even the fierce and brutal censorship of the prisons under the reign of communism,” comments the Ann Arbor sophomore.

While rooted in Albania’s past, similar to East European countries, ruled by a ruthless communist regime for half a century, Zhiti’s writing are in essence about humanity. As such, the Chicago based poet speaks directly to the audience regardless of their countries of origin or ethnicity. I asked Dr. Kola to tell me how students who are in their early 20s in a different time and space approach such themes. Dr. Kola acknowledges that “Although there are students in his class who have non-Albanian nationalities and come from different backgrounds, they are quite interested in the Albanian Literature of Exile course that encompasses the communist era 1944-1991. Also, each year, there are Albanian American students who are keen on the academic pursuit of the arts under totalitarianism and the diaspora literature.”

As for Rea Hajredini, who is of Albanian descent, Friday’s presentation by the guest speaker broadens our perspective on the subject of communism while elevating our understanding of one another. “I greatly enjoyed this event and was captivated by Zhiti’s experiences because I think that learning about the experiences of others allows us to become more aware and perceptual on the nature of communism and human experience, giving us the chance to empathize with others and learn from the past,” Rea notes. In terms of the biggest takeaway, she says is the power of love. The call To Save the Poems – the title of the talk – is the poetic and personal journey that starts within prison walls as an act of defiance in the face of extreme deprivation, and ends up overpowering darkness with light. “One of the greatest messages of Visar Zhiti’s presentation was when he remarked: “Let us remember that the most beautiful poem in the world is that of Love.”