Iva Gjoni

When thinking about tragedies, one would undoubtedly ask why innocent people die or how can one murder another because of his ideas. In reality, those who raised their voice—those who could not be silenced but expressed their opinions openly—were more courageous than those who killed them. Those who were not silenced and fought back to protect their rights are heroes.

My hero is Zef Pllumi, the Catholic priest who had an extraordinary education. In Live to Tell he writes this dedication: “To those that remained and died humans during that difficult period when man turned into a beast of burden.”

Zef Pllumi continues, “There’s nothing new under the sun. The water flows but the world remained the same. When I read the Bible or when I gaze at the pyramids in the desert, I ask myself how it is possible that the man of the XX century in the heights of its civilization is as barbaric as the man of forty centuries ago.”

I, too, ask why. How many lives were sacrificed in the name of lunacy? How many lunatics has the world known? Hitler, Stalin, Enver Hoxha. If there would have been a peaceful society where the people’s happiness is the sole aim and where the laws serve this purpose, surely human tragedies would have been avoided. However, every time period has its own heroes. What shocks me the most are the stories of innocent Albanians, intellectuals and elites, who were murdered in the name of an absurd ideology and propaganda. The dictator feared them, perhaps, and by eliminating freedom-loving people whose voices he could not silence, his reign would last longer. It is true that the people need leaders, but they need one who would truly lead, not using force and murder. Albania after World War II was like Goldwin’s Lord of the Flies, where a new civilization was beginning. The island’s “society,” wanting to escape from the war, find that their new leader is a murderer. He is the head of a powerful gang who, in the name of an unrealistic ideology that serves the rising dictator’s purpose, kills the intellectuals, subdues the weak, and fights the strong.

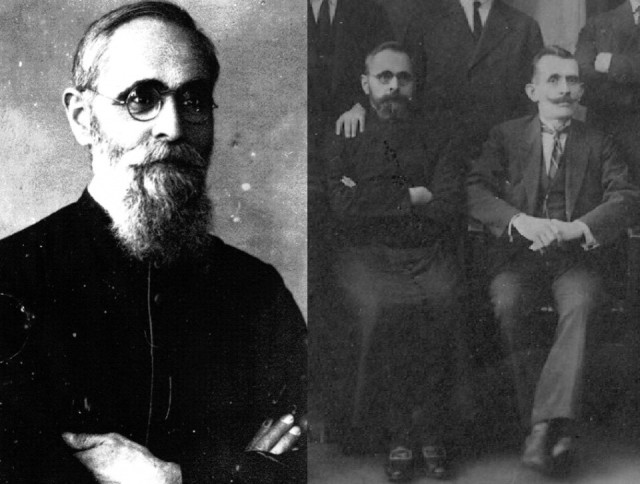

In this atmosphere Jul Bonati lived and worked; he was a philosopher, humanist, linguist, writer, translator, and Catholic priest who graduated from universities in Vienna, Austria and Padua, Italy. He served in Istanbul (16 years), Durres (10 years), and Vlora (3 years). Upon his arrest by the Albanian secret police, the suffering begins of Monsignor Jul Bonati of the Jesuits order, Vicar of Archbishopric of Durres, the Renaissance man and patriot. On November 6, 1946, he was arrested in Shkodra together with other Franciscans. In the trial against him, he said, “Our goal as religious men is to unite people in brotherhoods around the world. Catholicism’s enemy is the mistake, not the guilty; therefore, its enemy is communism, not the communists.”

Nevertheless, he was accused as an agent sent by the Vatican in collaboration with such figures like Vincenc Prenushi.

Professor Arshi Pipa, in Monsignor Vincenc Prenushi (in memoriam) (February 28, 1995), writes, “I remember an episode in the prison’s infirmary in Durres, where I was sent after my return from the camp of Vlocisht. There I found the Monsignor, who suffered from asthma. It was so severe that at times he could not breathe at all. Later, the parish priest of Vlora, Jul Bonati, was brought there. When he learned who was in the room with him, he got up from his bed and went to kiss the Monsignor’s hand. But the Monsignor pulled his hand. Instead, he gave Bonati his blessing and then collapsed in his bed.”

Jul Bonati was born in a well-known Albanian family in Shkodra on May 24, 1874. His parents were Aleksander Bonati and Roza Malgushi. (Roza Malgushi could have been from an Albanian-Venetian family in Corfu. Vaso Pasha’s wife was from the same family.) Bonati’s grandfather, Nikolla Bonati, was one of the founders of the Society of the Letters of Istanbul, founded on October 12, 1879, together with Ferit Pasha Vlora, Mehmet Bey Vrioni, the Frasheris, and Vaso Pasha.

After graduating from the Saverian College of the Jesuits in Shkodra, Jul Bonati entered the Jesuits as a novice in the province of Portore, in the regions of Fiume (in the border between Slovenia and Italy in 1891). After the consecration, he became a professor in Como, Soresina, Shkodra, and Istanbul. He became archbishop on August 14, 1912. At that time he was the parish priest of the Latin Apostolic Vicars representing the Albanian Catholics in the shores of Bosphorus, Istanbul. He was active in the Albanian War of Liberation. From 1920-1924 he was member of the Society “Albanian Eve” lead by Jonuz Bey Kolonja and Anastas Frasheri.

Vincenc Prenushi was sentenced to twenty years in prison; Bonati was sentenced to seven years in prison but, instead, he was placed at a psychiatric ward in Durres. Later he told his niece, who was able to visit him there, “I have suffered unheard of and unseen tortures. They have massacred me without reason in order to satisfy their soul …”.

Jul Bonati, fluent in several languages, the first translator into Italian of Lahuta e Malcis (The Lute of the Highlands, a long epic poem written by Gjergj Fishta, a well known Catholic priest), was found dead— “killed by senseless patients.”

Cardinal Claudio Hummes has said about such heroes, “These martyrs honor Albania because they give universal values to its people.”

(References: a biography by Aleksander Bonati, In the 135th Memorial of the Birth of Mons. Jul Bonati by Fritz Radovani, the writing of Besnik Mustafaraj at Opinion, and a French publication on great Albanian families.)

BOX

IL Liuto Della Montagna (Translated from Albanian into Italian by Mons. Giulio Prof. Bonatti)

Fragment: Canto V (La Morte) – Song V (The Death)

Se potessi saper che s’abbia mai

Oso Kuka, che il pane, questa sera,

Non gli va giù, nè di monton la carne.

Inutilmente in terra, presso al desco

Sta seduto, arricciando i suoi gran baffi:

Si dice ch’abbia fatto un brutto sogno,

La note scorsa, appena coricato.

Ha visto in sogno che da Rieka mosso

Un spettro di morte avvolto in fiamme,

Acceso in fiamme d’anima dannata,

Per il pian cammindano e la pendice,

Tra le paludi e su terren petrosi,

Difilato vinia verso Vranina. … …