By Ljudmila Cvetkovic, Radio Free Europe

The dozens of internment camps that sprung up in the former Yugoslavia are one of the most brutal and well-chronicled aspects of the Balkan wars of the 1990s.

Their discovery, early in the fighting, provided some of the most poignant and incriminating evidence that combatants were waging ethnic cleansing in newly won territories.

Now, a group of surviving detainees from one of the most infamous concentration camps in a Serb-controlled region of Bosnia-Herzegovina has filed suit in Belgrade to challenge televised statements downplaying its wartime horrors and mocking one of its most iconic inmates.

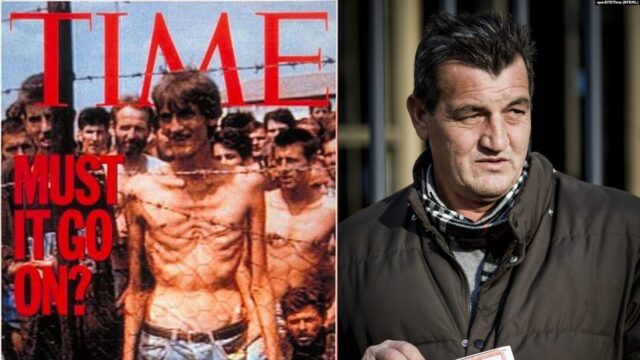

Plaintiffs include Fikret Alic, the Bosniak man who became a lasting symbol of Balkan atrocities after his skeletal frame was shown behind barbed wire at the Trnopolje internment camp near Prijedor, in what is now northwest Bosnia.

Alic, another survivor named Satko Mujagic, and the Association of Detainees from Kozarac are asking a Belgrade court to order Serbia’s parliament-appointed media regulator to reconsider complaints over the televised statements.

The comments in question were made on February 22 by the host of the Good Morning, Serbia program, Milomir Maric, and Predrag Antonijevic, who directed Serbia’s controversial Oscar candidate from 2020 about a World War II concentration camp, Dara of Jasenovac.

Maric suggested the images from Trnopolje fueled European “propaganda” early in the 1992-95 Bosnian War portraying Serbs as “the Nazis of the new age.”

He described Trnopolje as “an open camp” whose mostly Croat and Bosniak occupants “could leave…whenever they wanted.”

He added: “It was a camp to keep someone from killing them.”

Notorious Killing Field

The Trnopolje camp was one of three near Prijedor set up after Bosnian Serb fighters gained control of the area early in the war.

It was one of dozens of camps used to forcibly house or transfer Croats and Bosniaks in what is now Bosnia, including its Serb-majority entity, the Republika Srpska.

Prijedor was the theater of ethnic cleansing by Bosnian Serbs of an intensity overshadowed only by the Srebrenica genocide near the end of the war.

A victims’ association there says around 31,000 were detained at the Trnopolje, Omarska, and Keraterm camps near Prijedor over the course of the three-year conflict.

The same group says 3,173 civilians were killed there; a Sarajevo-based group puts the number of dead or missing in that area at closer to 4,900, the overwhelming majority of them Bosniaks.

UN war crimes trials established that Serb forces killed, raped, beat, and starved detainees.

Serb administrators removed Trnopolje’s barbed wire after its discovery by Western journalists and the international Red Cross in mid-1992, but guards patrolled the perimeter with automatic weapons and survivors testified that they feared they’d be killed if they left the camp.

Serb jailers misleadingly described it as an “open camp,” according to accounts cited by the United Nations.

The image of Alic, by British reporter Ed Vulliamy, appeared on the cover of Time magazine and helped alert the world to ethnic cleansing and other violence that would kill nearly 100,000 people in ex-Yugoslavia’s deadliest war.

Vulliamy, who became the first journalist since the Nuremberg trials to testify in a war-crimes trial when he appeared before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), would later describe Alic as “probably the most familiar figure in the world” during that long, brutal summer.

Antonijevic, on Serbian TV, described Alic dismissively as “the one with tuberculosis, the one who was thin, right?”

“And they fed him afterwards — they took the skinny one away, [and] they showed him in a circus in Europe, that’s their propaganda,” Maric said.

Say Anything?

Serbia’s Regulatory Authority for Electronic Media (REM) ruled in May against official complaints by Alic and the other plaintiffs in the current appeal as well as by the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, an NGO.

The REM said there was insufficient support for the plaintiffs’ argument that Maric and Antonijevic violated basic human rights, insulted the dignity of victims, or misled the Serbian public through false information that could further divide ethnic communities in Serbia and the former Yugoslavia.

It acknowledged that the references to Alic were affronts to him personally but said the broadcast never denied the existence of the Prijedor camps or crimes committed there subject to war crimes verdicts in The Hague.

In the end, the authority announced, the REM’s leadership council proposed a warning and a 30-day ban or suspension of proceedings, but “since none of the proposals received the required majority of votes, the vote led to the suspension of the procedure.”

The survivors’ lawsuit seeks to annul the REM’s decision and force the watchdog to render a binding decision on whether the TV Happy program violated the law or not.

“If they were open camps, I don’t know why there are mass graves from those camps and so many killed inmates,” Alic said.

Alic, who was caught in his house, detained, and imprisoned soon after the outbreak of war in 1992, survived the Keraterm and Trnopolje camps and has remained an outspoken advocate of justice for the victims of Serb forces.

“I’m not a circus performer,” Alic told RFE/RL’s Balkan Service, “I’m an ordinary man and, like you and I and all citizens, when we are cut, it hurts the same way.”

He said justice should include an end to “spitting on ordinary people.”

Still Deep Divides

Questions of war guilt are still deeply fraught throughout much of the former Yugoslavia, whose disintegration after the fall of communism sparked multiple wars that killed at least 130,000 people and displaced millions.

Maric, a longtime journalist who hosts several programs for the commercial TV Happy network, said that his only sin was to have said it was impossible to compare the Prijedor camps with the World War II extermination camp at Jasenovac, which was run by a Nazi quisling regime in Croatia known as the Ustase.

“I neither denied the crimes in Prijedor nor insulted the victims in any way, and I said about Fikret Alic what I read in the Western European press,” Maric told RFE/RL.

He acknowledged that he may not have chosen his words “carefully” and noted it was a live broadcast.

Antonijevic’s film, Dara of Jasenovac, was a controversial choice within Serbia for nomination in the best foreign film category for the 2021 Oscars.

A seemingly indirect effort at diluting ethnically based atrocities committed a half-century after World War II, it was variously described by Western critics as agenda-based.

Many observers noted its sharp contrast to a Bosnian entry that was shortlisted for the same prize, Quo Vadis, Aida?, which followed the 1995 genocide against Bosniaks by Bosnian Serb forces in Srebrenica through the eyes of a UN translator.

Written by Andy Heil in Prague based on reporting by RFE/RL Balkan Service correspondent Ljudmila Cvetkovic in Belgrade